Please turn on sound.

Our research into snowflakes has revealed a number of interesting facts:

The lowdown on snowflakes

- There are two ways for a snowflake to form: either pure water vapor freezes into ice particles in supercooled air or, more commonly, frozen water particles stick to dust particles in clouds and freeze. Other water particles then freeze at the corners of the tiny ice crystals, causing them to grow – and snowflakes to form. At some point, these flakes become so heavy that they fall from the sky.

- Every ice crystal is unique, with prisms, columns, platelets, needles and star-like structures forming as they become snowflakes. They almost always have a six-pointed shape. The underlying structure stems from the arrangement of the water molecules and the countless ways they can be reconstituted. No two crystals are the same.

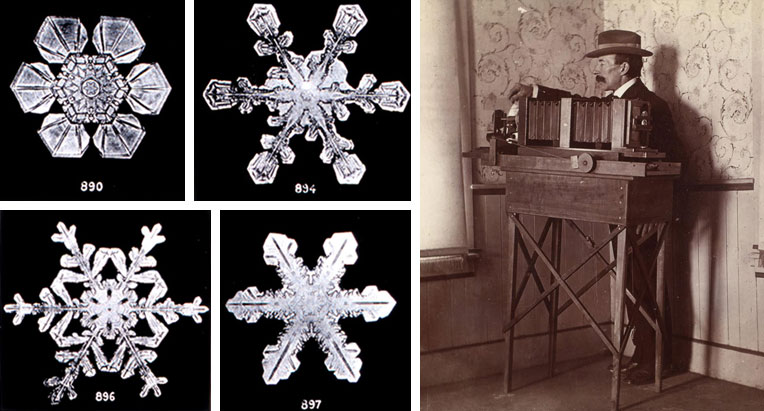

- The US-American Wilson Bentley was a well-known researcher of snowflakes. In 1885 he was able to attach his microscope to his camera and photograph a snowflake. The physicist Ukichiro Nakaya made his name by creating the first artificial snowflake.

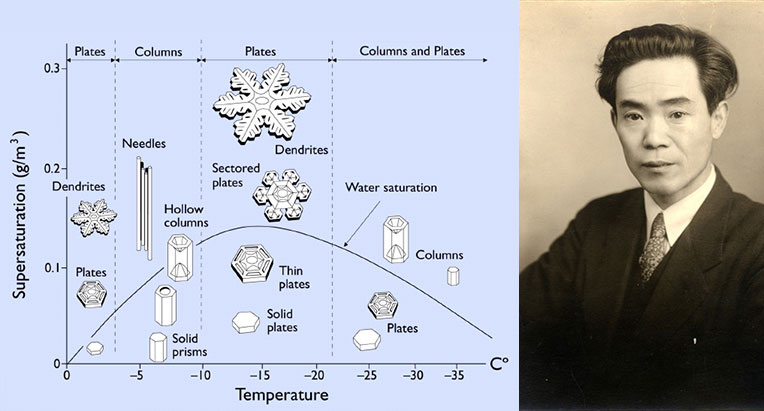

- A snowflake constantly changes and acquires its unique shape during its one- to three-hour journey from the clouds to the earth. Atmospheric conditions such as temperature and humidity influence the shape it takes later on. While snowflakes that form at minus 15 degrees Celsius are almost perfectly symmetrical, those that crystallize at minus seven degrees tend to consist of cylinders, needles and prisms of ice. The higher the water vapor content in the air, the more complex and delicate the flake’s structure will be.

- According to Guinness World Records, the largest snowflake in history was 38 centimeters wide and was purportedly seen by a farmer in the USA in 1887. At least 275 water molecules have to combine to trigger the creation of an ice crystal. A crystal visible to the human eye contains around one trillion molecules in total – that’s a 1 with 18 zeros after it. Many crystals combine to form a snowflake whose size may vary depending on the weather conditions.

Sources: fm1today.ch / derstandard.at

Caption: Snowflakes photographed by Wilson Bentley. (NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS), Vermont, Jerichot / Imago)

As the world now knows, snowflake expert Wilson Bentley was not the first to photograph a snowflake, but his photos have lost none of their magic to this day. In his 1931 book, “Snow Crystals”, he published 2,400 of the 5,000 snowflakes that he captured on celluloid. He left his photographic plates to the Buffalo Museum of Science.

Source: aargauerzeitung.ch

Caption: Ukichiro Nakaya realized that temperature and humidity are two contributing factors that cause every snowflake to develop differently. (zvg)

Ukichiro Nakaya, a Japanese physicist and science essayist known for his work in glaciology and low-temperature sciences, started researching the phenomenon in Japan in 1933. He took around 3,000 photos of natural ice crystals, then subdivided these crystals into 41 basic forms with seven main types based on their appearance. In other words, the closer one looks at a snowflake, the more unique it becomes. The Japanese scientist’s graphic work continues to be cited as the “Nakaya diagram” in specialist literature today.

Source: fm1today.ch

For almost 20 years, Henning Löwe (Head of Group Snow Physics at WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF) in Davos) has researched the physical properties of snow and related changes in its structure. Thanks to technical advances and global partnerships with institutes such as the European Space Agency (ESA), more and more data is being made available to researchers. It was thanks to his collaboration with the ESA that Henning Löwe was able to gain insight into an extremely unusual crystal shape for the first time. A Danish researcher sent him a snow crystal shaped like a piece of macaroni, which formed at an extremely low temperature. Does it share anything in common with a regular crystal? Yes, actually, because the atoms, molecules and ions that make up snow crystals are arranged in uniform structures. Still, our romanticized notion of what a crystal should look like favors the classic “platelet” snowflake shape. By contrast, prism-shaped rods, needles or macaroni forms tend to blunt the appeal of a snowflake.

While snow crystals may vary in shape, they do share one thing: their six-fold symmetry. As Henning Löwe states, “You would have to go to a different planet to find other symmetries.” In other words, we’ll have to content ourselves with the hexagonal forms found on Earth. And break out the magnifying glass to hunt for macaroni amid the snow.

Source: aargauerzeitung.ch